Earlier this week I wrote about some of the exciting polaritons in semiconductors. And just a few days later, there is another intriguing paper on this topic out. Something that I speculate(!) might lead to new types of quantum computers.

But to recapitulate, polaritons are object that form when light interacts with electronic excitations. What I also mentioned was that if cooled down to about 30 degrees above absolute zero the polaritons for a condensate. In this condensate all polaritons are identical — they oscillate synchronously. Mathematically, they all have the same phase.

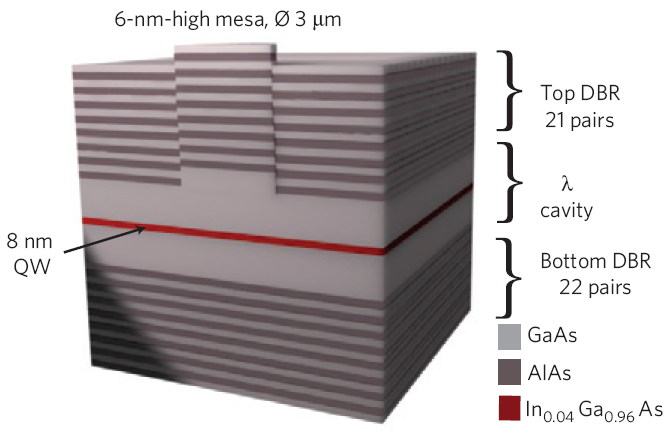

Typical semiconductor structure in which polaritons can be created. Two mirrors (DBR) on top and bottom of the device confine light between them. In the center is a layer (red) where the high light intensity between the mirrors creates polaritons. In the present study two such layers are placed right next to each other. Image reprinted by permission from Macmillan Publishers Ltd: Nature Materials 9, 655 (2010).

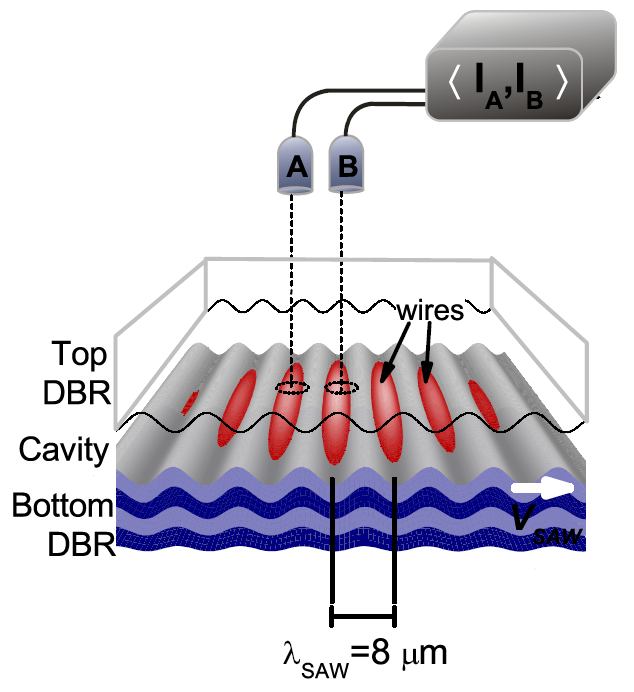

In my last blog post, I described how acoustic waves can separate this condensate into thin wires. What Benoit Deveaud-Plédran and colleagues from the École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne in Switzerland have now realised is along the same idea: they fabricated two polariton condensates right next to each other.

What happens if the two thin layers with polariton condensates come close to each other? Something very similar to what superconductors do. The particles in superconductors also are in the same quantum state, with the same phase. And what we also know is that if two superconductors are brought in close contact to each other and if an electrical voltage is applied across the barrier that separates the two, an electric current flows. But unlike the static current of normal conductors, for superconductors it shows a characteristic modulation: the magnitude of the current that flows oscillates over time. This is the Josephson effect.

September 17, 2010

1 Comment