As this week there is again a lot of talk about journal impact factors with the release of this year’s data later today, I like to take this timely opportunity to look at citation metrics more broadly, in terms of fundamental flaws in weighing data, and important data missing in the underlying data sets, which in my view miss important data when it comes to practical, technological impact of a study.

I recently had the opportunity of attending a talk by Paul Wouters from Leiden University, a professor of scientometrics. He pointed out one of the fundamental flaws in citation metrics that goes right to the heart of such data collection, before one should even discuss more superficial metrics such as h-index or the impact factor. Like any other piece of data, the context of a citation matters, he said. Factors that play a role are the type of paper where a reference is cited, and in what way. Was it criticism? Controversial papers for a while at least can gather a lot of citations even though eventually their impact on scientific process can be nil. There are also human aspects. Relevant points here are who cited a paper, was it a self-citation, or were there other motivations for citations? After all, citation cartels are not unheard of.

There is a lot of literature on various aspects of citation analysis, and more details on this can be found in Wouters’ doctoral thesis on citation culture, or in the 2008 paper by Jeppe Nicolaisen on citation analysis.

More broadly speaking, I am not sure whether it will be possible to properly analyse and process context when it comes to citation analysis. There are too many ways to game such systems. However, a more complex analysis might well be possible, taking the example of he ranking of web sites in search engines. There, context is everything. A website that is linked from many other sites is not necessarily an important one. Instead, a link to a web site from an important web outlet such as a popular news web site weighs much more than links from unknown web sites. Indeed, many links from news web sites or social networks might also be an indicator of immediacy, further propelling a site up the search engine rankings. […]

Continue reading...

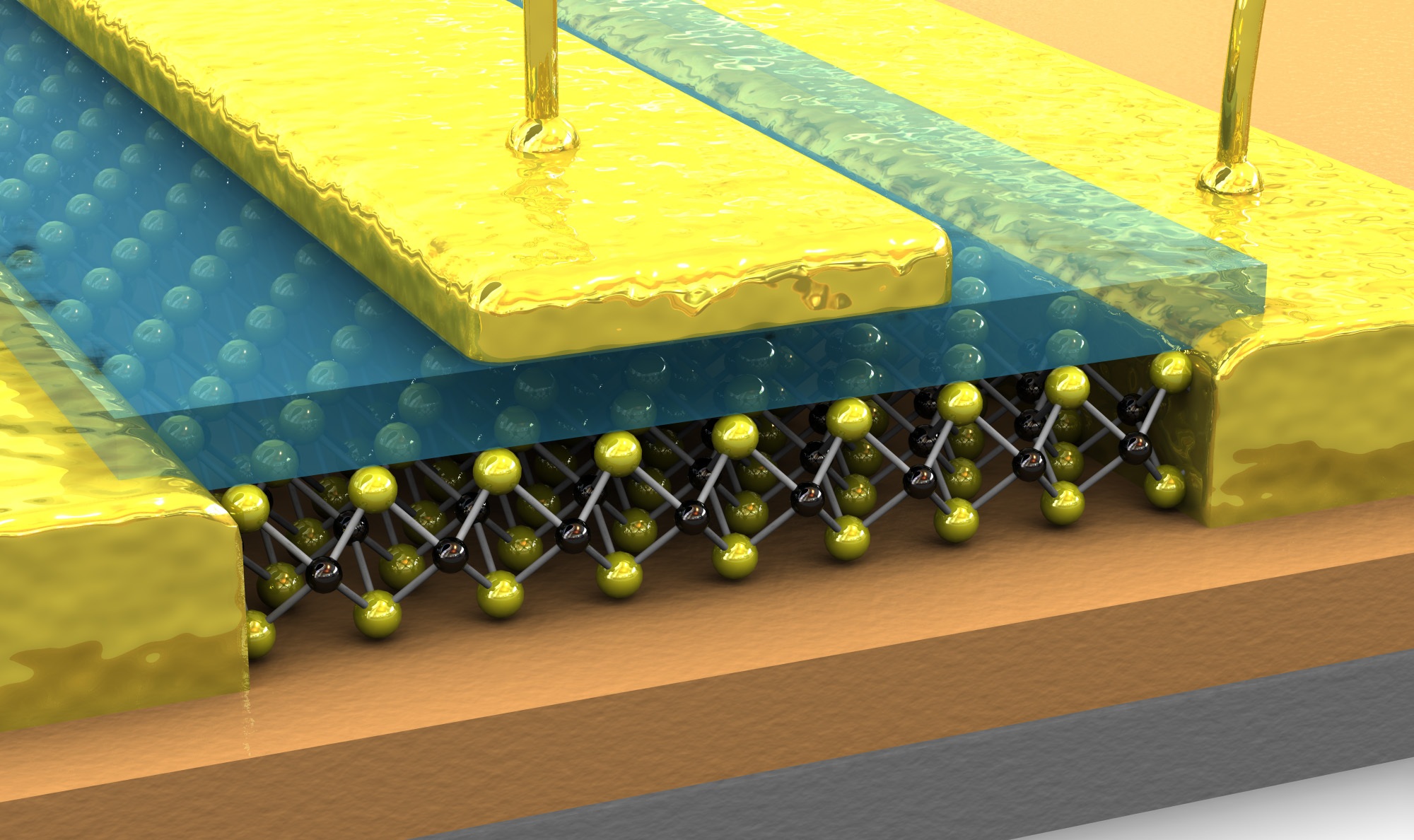

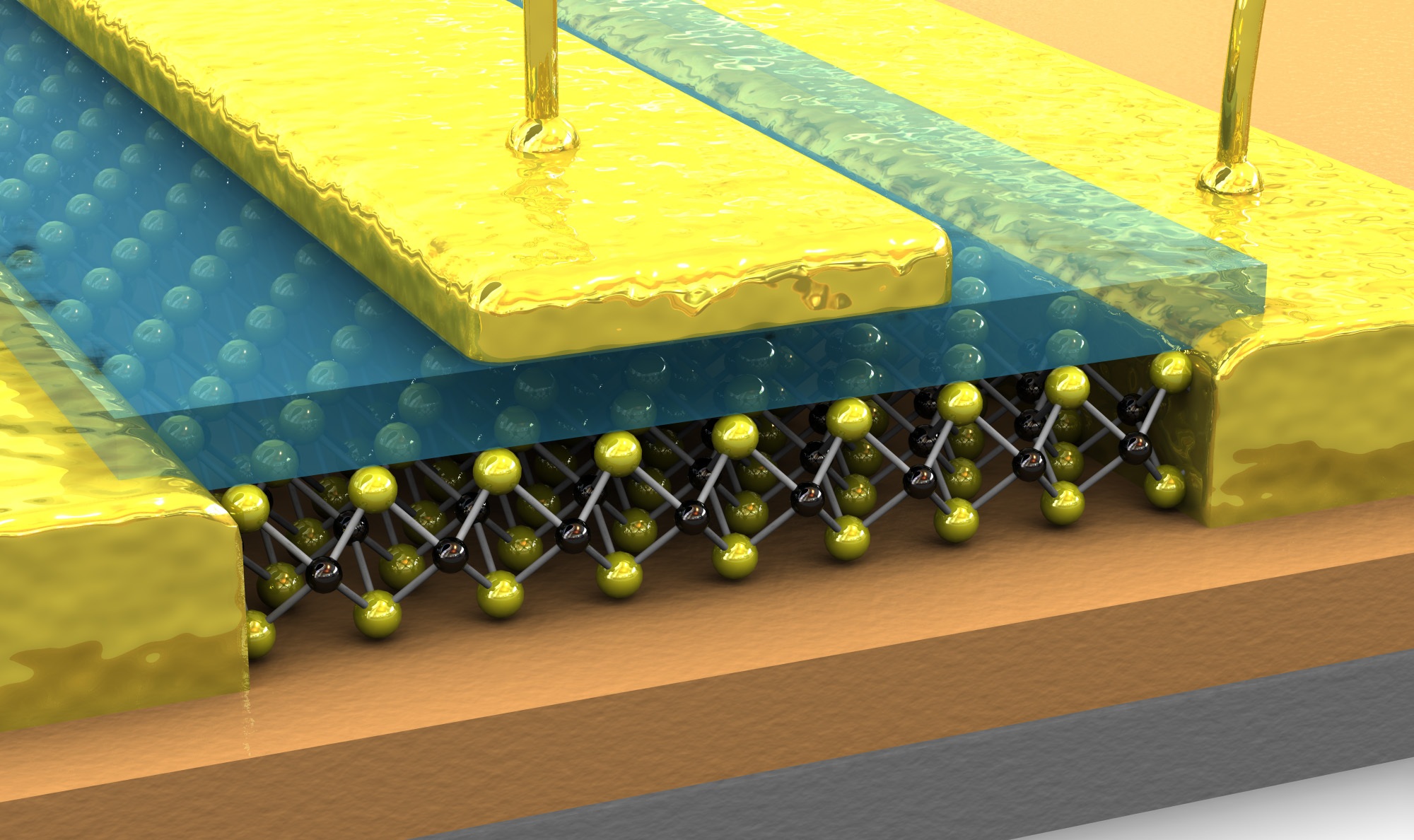

A beautifully looking graphics, isn’t it? But there is a major caveat. As its creators would agree, this image is only a very crude depiction of reality and shouldn’t be used for any scientific purpose… (c) LANES, EPFL

Nanotechnology is a wonderful science that has pushed functional devices to sizes not far away from the size of atoms. So small that if you want to image such structures, even a conventional electron microscope wouldn’t get you far. There is no way to directly see what is going on. This is a common problem. Take condensed matter physics – it is impossible to directly visualize the various interactions and events taking place inside a crystal. Or photonics, where complex light fields interact with tiny nanostructures in ways that can be really difficult to visualize, especially in real-time.

So, no wonder that artificial graphics often serve to illustrate a scientific concept or a certain device. And with the prevalence of advanced computer graphics programs such illustrations are becoming more and more fancy. In my opinion, this is a dangerous trend, because such graphics can distort the underlying science they try to depict. […]

Continue reading...

The young Max Planck, when completing his high school degree, asked a professor of physics at the University of Munich, Philipp von Jolly, whether he should study physics. He got the famous answer that this wouldn’t make much sense, because physics is an almost fully mature science with not much to discover. (If you happen to speak German, it is worth reading the original text, reprinted in this biography of Max Planck.)

Of course, luckily Planck ignored this advice and went on to make some of the most profound discoveries in modern physics. And well, if you think we are in a similarly dull situation in physics at present, the past few weeks would have certainly disproved this, because a couple of intriguing, unpublished (in the academic sense) research findings have appeared widely in the news: neutrinos that continue to appear to be faster than the speed of light, a completely new view on wavefunctions in quantum mechanics, and it seems also that there isn’t much hiding space left for the Higgs boson, if it exists.

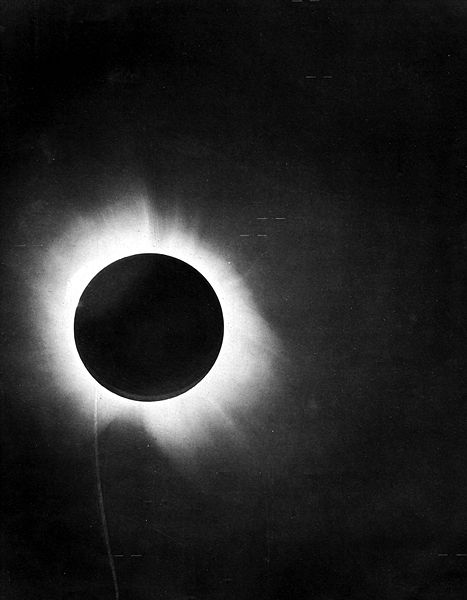

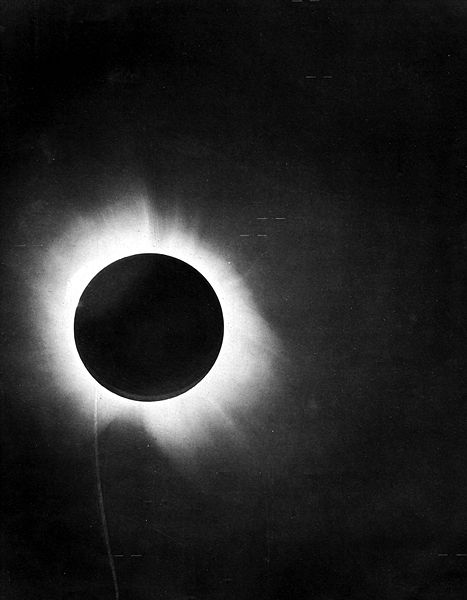

Arthur Eddington's 1919 photograph of the sun during a total eclipse. The position of the stars appearing behind the sun verified Einstein's theory of relativity. Photo via Wikimedia.

Those discoveries all come with the promise of significant changes to our understanding of physics, and we’ve seen some exposure in the news (and the occasional hype, too). This is perhaps not surprising. The neutrino experiment questions the theory of relativity. The absence of the Higgs boson on the other hand would open the question again about the different masses of particles. And the new view of wavefunctions seems to add further to the arguments whether the wavefunctions in quantum mechanics are purely an expression of probability to find an object in a certain physical state, or are a representation of actual reality. The paper now rules out the possibility that wavefunctions are probabilistic states, but still having an underlying reality. Instead, there are two interpretations left. One can either fall back to the argument that there is no underlying reality in quantum mechanics and wavefunctions simply are nothing but probabilistic. Or, the second option is that wavefunctions are an expression of actual reality, abandoning the probabilistic interpretation. Not surprisingly, for this reason the paper got lots of headlines. Most people my colleagues at Nature spoke to were quite enthusiastic, whereas Scott Aaronson didn’t seem to see that much of a surprise. Matt Leifer has an informative, quite detailed description of the paper on his blog. […]

Continue reading...

July 29, 2014

Comments Off on Citations and the problem of capturing impact