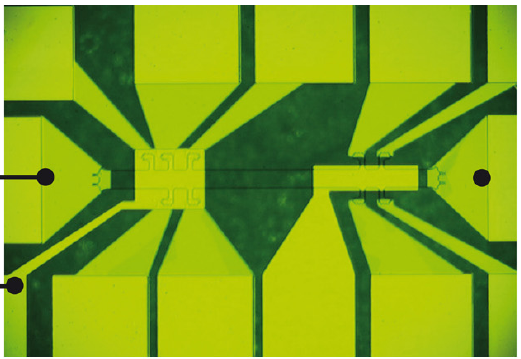

This USB flash drive used a bulk metallic glass for its casing. Credit: Liquidmetal Technologies.

This week I am attending the 2010 Materials Research Society Fall Meeting in Boston — one of the key meetings in materials science. One of the sessions is on bulk metallic glasses and their applications, which this year is a little special. It is organised in honour of the 50 year anniversary of the first demonstration of a metallic glass by William Klement, Ronald Willens and Pol Duwez from Caltech. Their paper on gold-silicon alloys was published in Nature on September 3rd, 1960. (In addition to Duwez and colleagues, David Turnbull must be mentioned here as one of the pioneers with several key contributions to the field. For example in 1948 he demonstrated that metals can be considerably undercooled below their crystallisation temperature.)

Metallic glasses have since become very interesting for applications that include sports products, coatings, power transformers where they reach several ten thousands of metric tons annual production, sports equipment, bioimplants and others. At the same time research researchers still try to learn more why these glasses form in the first place.

Why are metallic glasses so special?

All metals prefer to form crystals, as the metal atoms easily form structured bonds with other atoms. So easy in fact that even when the metal is melted some of that arrangement carries over into the liquid. This makes the formation of a crystal the preferred pathway once the melt is cooled down again. Glass on the other hand is amorphous, which means that the atoms are disordered and there is no long-range periodicity. This is not something metals prefer. Unlike the window glass made of silicon oxide. In comparison, metallic glasses are a very different animal. […]

November 30, 2010

3 Comments