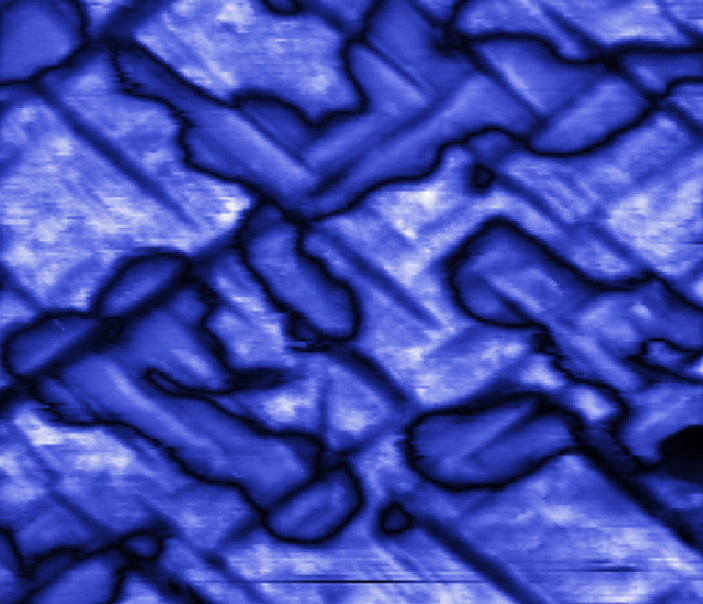

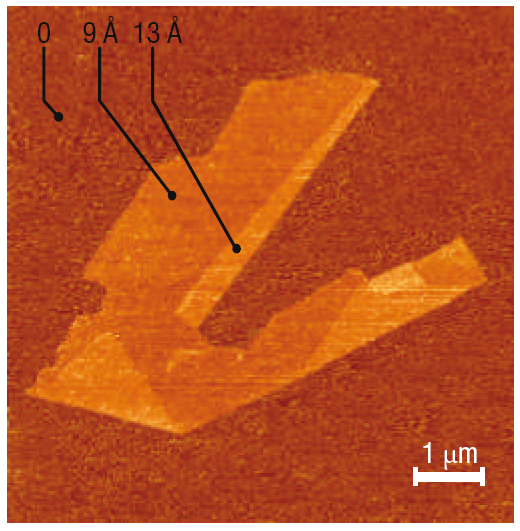

Domains in a ferroelectric material, where electric charges have a different orientation. Here, there are two separate sets of domains. The cross-hatched patterns indicate domains in the plane, the rounder shapes are domains where the polarization points out of the plane. Reprinted by permission from Macmillan Publishers Ltd. Nature Materials 7, 209-215 (2008).

Insulators might seem pretty boring materials for an electronic device such as a computer memory, because by the very nature of their definition, they don’t conduct any electrical current. But some insulators show some pretty intriguing properties. Amongst them are the so-called ferroelectrics.

Dipoles in a ferroelectric. During switching, positive and negative charges interchange.

A ferroelectric is a material where positive and negative electrical charges, are permanently separated along a common direction. These are the positive and negative ions that make up the crystal. Their order leads to an overall electrical polarization of the material. This can only happen in an insulator, because if the crystal would enable electrical charges to move around the separated plus and minus charges could be compensated easily by such movements of electrons.

In some special materials, ferroelectricity and magnetism occur simultaneously. These are known as multiferroics, and I blogged about their potential applications before. In particular, the dipoles in a ferroelectric can be switched by an electric field, which makes them attractive for electronic applications as ferroelectrics can be used to permanently store information as a new form of computer memory.

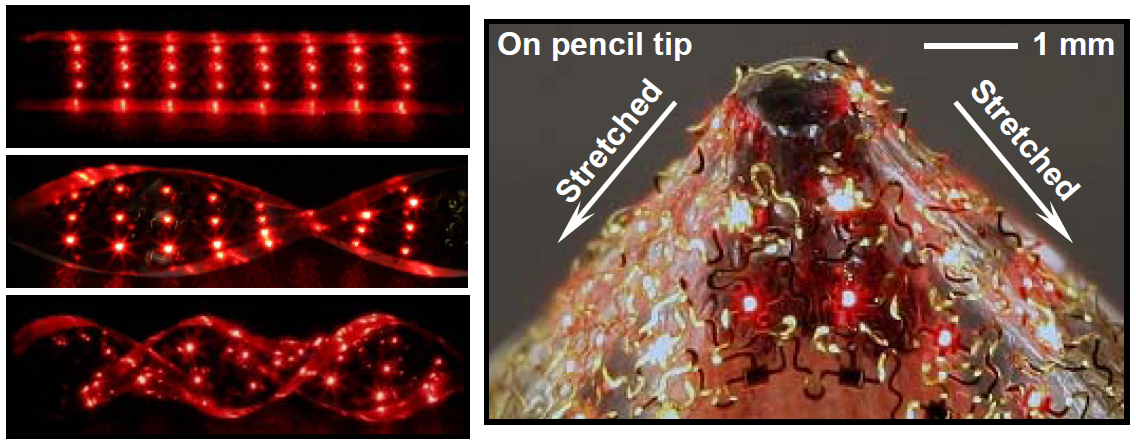

But how can the electric polarization in a ferroelectric be switched? There are two options. One mechanism is similar to what happens in a magnet. If an electric field is applied, new domains with a polarization aligned in direction of the external field form (see figure below). These domains gradually replace the old ones. This process is abrupt, because as the new domains expand, the ions in the crystal swap places in a single process.

The second possibility of switching electric polarization is a continuous mechanism. There, the positive and negative ions move slowly in opposite direction. First, the electric polarization weakens, vanishes, and then builds up again in opposite direction. This process occurs without the involvement of any domains. Of these two processes, the domain-based switching is far more favourable, which is why the switching process without domains hasn’t been observed before. Two independent papers now both claim to have seen switching without domains. […]

October 28, 2010

5 Comments