Metamaterials are very exciting structures, one of the most exciting areas in photonics, I think. That’s because they allow an almost arbitrary modification of light (or acoustic) waves propagating through the material. Sadly, however, the highly promising potential of metamaterials gets often completely overblown by news reporting on fantastic effects. Cloaking devices are the prime example. Here I try to come up with a few points that might help to sort science from fiction.

Metamaterials are small metallic structures, typically rings or wires, that locally change the materials properties. These structures are much smaller than the wavelength of light. To a light wave, it is as if the structure is not made of tiny rings and wires, but looks like a homogeneous material. Hence their name ‘metamaterials’. Meta is Greek and means beyond. The first metamaterials all used the same small units of wires and rings, repeated over and over. With this, you can achieve a negative index of refraction, which enables superlenses – lenses with perfect resolution.

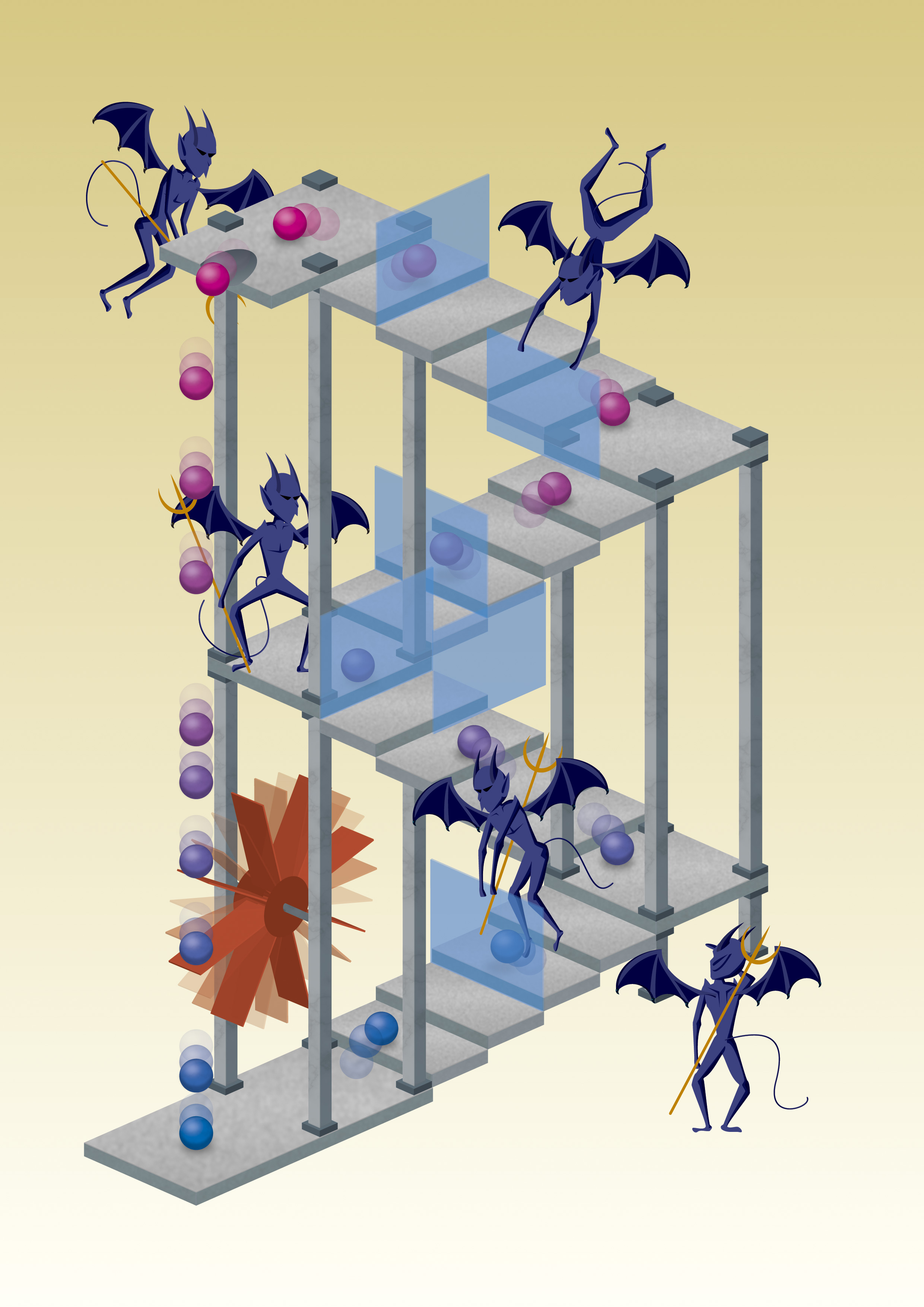

The original metamaterial designs consisted of electromagnetic resonators made of rings and wires. These devices are for THz and GHz radiofrequencies. Credit: NASA, via wikimedia

The next key advance was that metamaterials needn’t only consist of uniform assemblies of rings and wires. If you change the properties of each unit of a metamaterial, you can create a material that to light looks as if it changes its properties. This way it is possible to modify the propagation of light as it goes through the metamaterial. You can make it go round corners, turn it around. In theory, the possibilities are nearly endless, that much is clear.

The prime example to demonstrate the possibilities of metamaterials is the optical cloak. The term is borrowed from the science fiction series Star Trek. And naturally, it is these kind of visions that let our fantasy go wild when thinking about metamaterials cloaking. Images of Star Trek, or ‘Harry Potter cloaks’ and the ‘invisible man’ are often conjured when journalists, university press offices and even scientists try to explain metamaterials to the public. Sadly, in relation to what metamaterials can do, this is nonsense.

So here are a few things that metamaterials can and cannot do.

November 16, 2010

10 Comments