Light is special. In our everyday experience it behaves like a wave, which gets reflected, refracted and shows interference with other light of the same wavelength. At the same time, light also consists of particles, so-called photons. This duality is quite fundamental: the Hanbury Brown and Twiss experiment for example only works because of the particle-like properties of light.

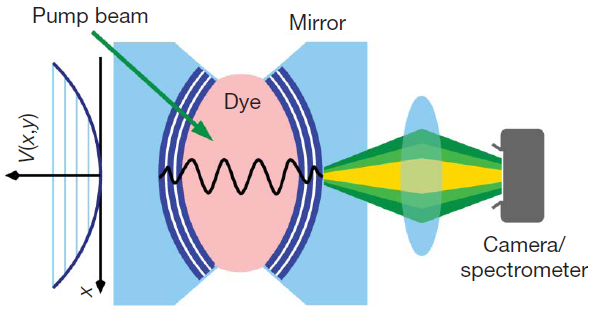

The experimental setup. A laser beam injects photons into a cavity filled with light, and a camera observes the photons coming out of the cavity. Reprinted by permission from Macmillan Publishers Ltd. Nature 468, 545-548 (2010).

This amazing and perhaps confusing duality, where light in one experiment appears to be a wave and in others it behaves like particles, is now laid bare in a paper published in Nature. There, Jan Klaers, Martin Weitz and colleagues from the University of Bonn in Germany take one of the classical properties of light waves and turn it upside down — by demonstrating a related effect that only works when considering the particle qualities of light!

The classical effect they use is that light waves can all oscillate synchronously. This is exactly what happens in a laser, and is typical behaviour for a class of particles to which photons belong to, the bosons. Bosons love to be all in the same state.

A similar synchronous behaviour can also occur for other bosons, including certain atoms, which then all assume the same quantum state. This state is called a Bose-Einstein condensate, after Satyendra Nath Bose (after whom bosons are named) and Albert Einstein, who described it first in 1924. It is a Bose-Einstein condensate of light that Weitz and colleagues have now demonstrated. […]

November 24, 2010

2 Comments