The study of materials is one of the major areas of science, with legions of researchers in physics, chemistry and materials science working on this topic. Condensed matter physics is one of the largest research areas in physics. Yet, it makes me often uneasy how the benefits of materials science are promoted. It is all too often about applications, and not about fundamental physics. How materials such as graphene might revolutionize electronics. And how new physical concepts could be used to develop materials for energy applications: solar cells, batteries and so on. In classical materials science it’s often about tougher materials, such as enhanced steels, and less about the fundamental insights they are based on. Of course, applications are an important aspect in the study of materials. But does this mean that too often fundamental insights are neglected in favour of a material’s commercial potential?

Tag Archives: ILL

Gravity weighs in on spectroscopy

April 17, 2011

The visible spectrum of neon and its characteristic emission lines. By Jan Homann via Wikimedia Commons

In 1814 the German physicist Joseph von Fraunhofer observed narrow dark lines in the otherwise continuous spectrum of light emitted by the sun. Hundreds of them. As Gustav Kirchhoff and Robert Bunsen later showed, these lines correspond to the absorption of light by various chemical elements in the sun. Each element has its own unique set of lines that correspond to energetic transition between the electronic states of these atoms. This discovery has laid the foundation to the field of spectroscopy, where the interaction of matter and light is probed.

A study published in Nature Physics this week by Hartmut Abele and colleagues from the University of Vienna in Austria now reports how gravity can be used instead to probe quantum states. And they’re not using atoms either, but neutrons, which are the electrically neutral particles in the atom’s core.

These neutrons are produced in nuclear research reactors, for example at the Institute Laue-Langevin (ILL) in Grenoble, which I visited last year. In fact, the experiment by Abele and colleagues was done at ILL because there ultracold neutrons are available for research – “still the only source of ultracold neutrons for users in the world,” says Peter Geltenbort from the ILL, who took part in the experiments. […]

The very fabric of research: a visit to the ILL in Grenoble

September 20, 2010

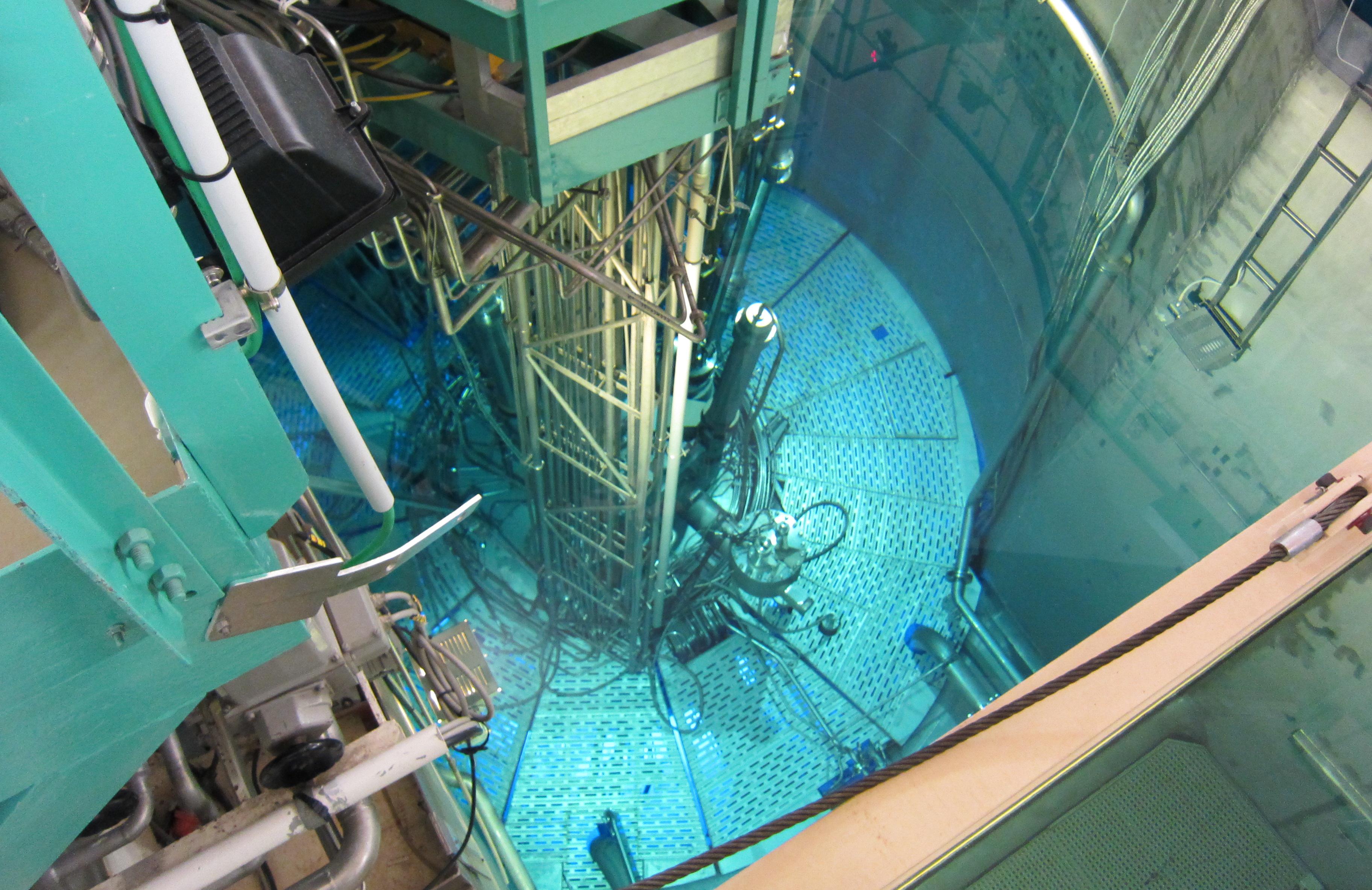

The nuclear reactor at ILL. The nuclear fuel is underneath the steel shield. The blue glow of that is partly visible is caused by Cerenkov radiation.

You look down into a clear pool of water. The water has an appealing blue glow to it that makes you want to dive into it. But this isn’t a swimming pool, it is a nuclear reactor. And the soothing blue glow is not due to the blue paint of the pool walls but caused by the Cerenkov radiation, emitted as a result of the electrons created by the fission process that move faster than the speed of light in water.

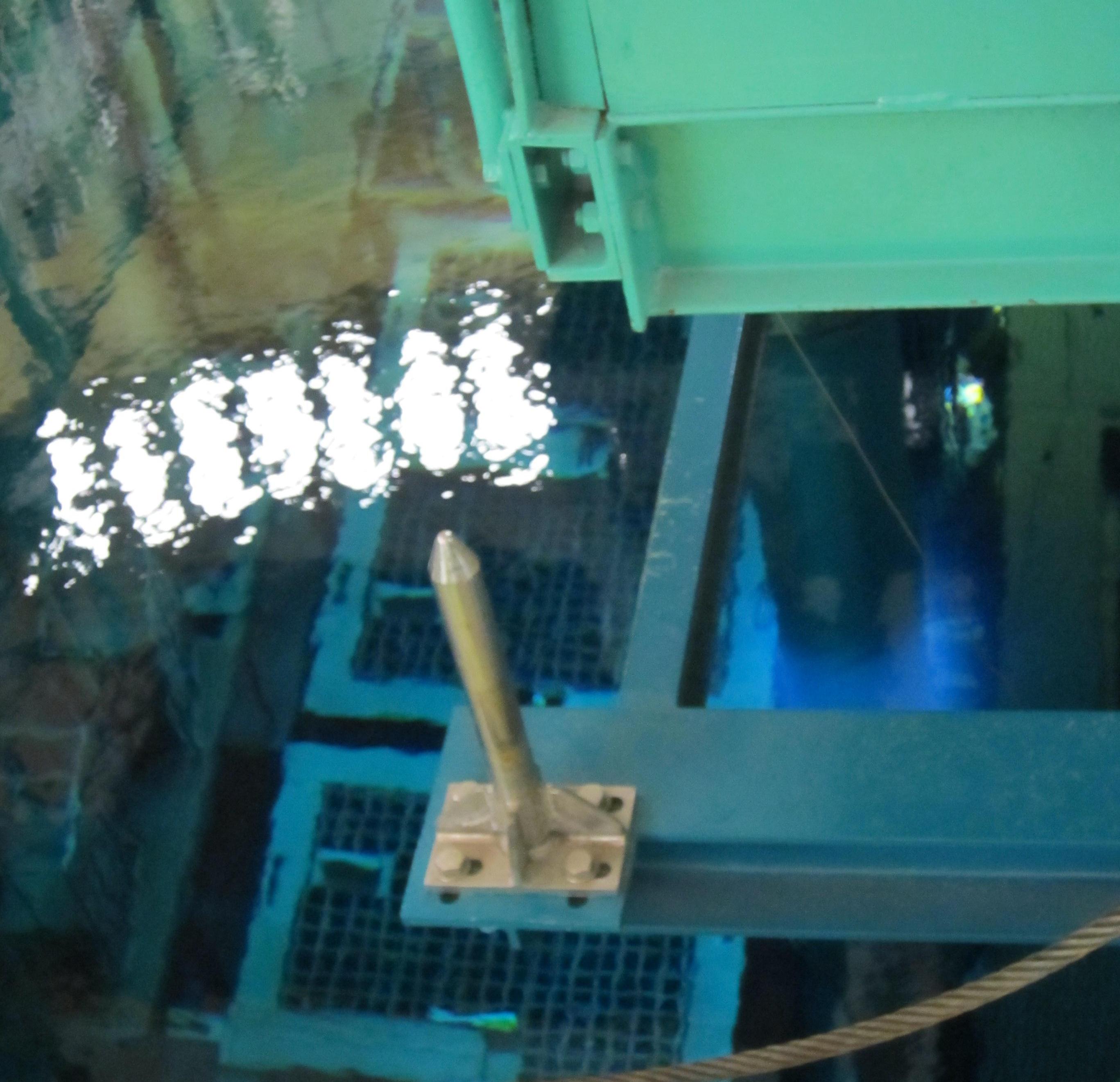

The electrons that are ejected from the nuclear fuel elements are fast than the speed of light in water (about 75% of the speed of light in vacuum). Similar to the supersonic bang of jets that fly faster than the speed of sound, Cerenkov radiation is emitted by water as the fast electrons pass through it. The blue shimmer of the Cerenkov radiation is visible on the right of the photo, showing the pool containing spent reactor fuel.

The reactor I am visiting is that at the Institut Laue-Languevin (ILL) in Grenoble. As a research reactor it is generating up to 58 megawatts of power, about 25 times less than that of commercial reactors. Still, I am nervous holding my camera directly above the pool to take pictures, afraid I might be dropping it into the running reactor. But there is no need to worry, it is safe to stand there, the water is a perfect shield from the radiation, it absorbs all the neutrons and electrons created by the nuclear reaction. And there is of course plenty of security and radiation monitoring before, during and after my visit. Even if I would drop the camera into the pool, there is a steel construction in the water that would catch larger objects. And stuff that would slip through that grid would probably lie harmlessly at the bottom of the pool until the reactor is decommissioned.

Not many people are allowed inside the reactor and I am lucky enough to be invited to the ILL along with a few British colleagues. It is only the second time I am inside a nuclear reactor. It is an awesome feeling, certainly for a physicist, to see an operating reactor and to admire the technology that keeps the nuclear chain reaction under control. The impressions from my visit not only reinforce what I know about the benefits of neutron research, but the variety of research to me also underlines the dangerous implications of possible recession-related government budget cuts to facilities like ILL.

ILL was founded by France and Germany in 1967, with the UK becoming a third major partner in 1973. Initially, the UK did not join the institute because it wanted to build its own reactor, tells us our tour guide, Andrew Harrison, an Associate Director of ILL. Nowadays it seems almost unbelievable to me that the UK abstains from a European research project because it intends to invest more money into a certain area of research, not less. In any case, today, Germany, France, and the UK still share 75% of ILL’s operating budget of 88 million Euros, the rest being distributed amongst its other international partners. Their continuing support has made ILL one of the leading research institutions that uses neutrons for experiments in life sciences (18% share of experiments), environment (11%), materials science (29%) and fundamental sciences (35%).

November 7, 2011

5 Comments