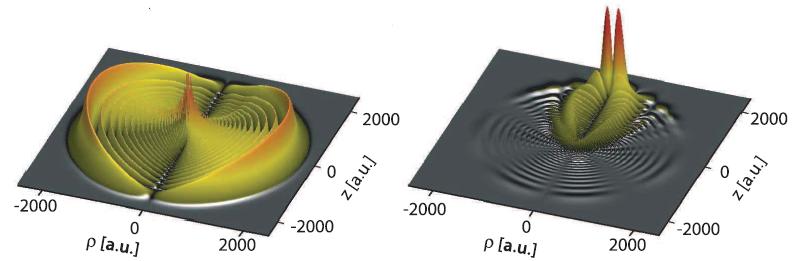

Permanent electric polarization. Left: the electron density of the rubidium Rydberg electron in one of the atoms of the molecule. The asymmetry is hardly visible. Right: The same electron density, but with the density of the Rydberg atom on its own subtracted. The difference clearly shows an asymmetric distribution of electrons roughly at the position of the second rubidium atom, causing an electric polarization. (c) 2011 Science Magazine

Apply an electric field to a material, and its positive and negative charges will separate, creating an electric polarization. This is the fundamental effect behind capacitors used in electronics as well as in ferroelectrics used in some computer memories. In the latter case, to achieve a permanent electric polarization, the positive and negative charges need to be shifted permanently. This is the case if in a crystal all positive and all negative ions in a crystal are shifted in the same way with respect to each other.

The separation of positive and negative ions in a crystal can lead to a permanent electric polarization. A similar effect has now been achieved with electrons.

In a paper in Science from last week, researchers from the group of Tilman Pfau at the University of Stuttgart in Germany with colleagues from a number of other institutions have now demonstrated an entirely new way of achieving permanent electric polarization – namely by using electrons and not ions. This effect is remarkable, because electrons usually are much more mobile than atoms. Normally, any charge imbalance in the electron distribution of a material or molecule is easily neutralized simply by shifting electrons in the molecule around. At the same time, looking far ahead, such electron-based effects could lead to applications where the electric polarization needs to switch ultrafast.

However, the molecule studied by the researchers is quite different to usual molecules. It is formed by two rubidium atoms, which means that normally it should not show any electric polarization, simply because both atoms in the molecule are identical and for symmetry reasons no positive or negative ions would form in the first place.

But although they are both rubidium atoms, here there is a crucial difference in the electronic states. One of the atoms is in its energetic ground state, while the other is a so-called Rydberg atom, which means that its outermost electron is excited into a very high energy state and circulates the atom’s nucleus at a large distance. Rydberg atoms are huge in comparison. Here, the rubidium atom is roughly about 50 nanometres in size, corresponding to about 1,000 times the size of a oxygen molecule – and is larger also than the transistors in modern computer chips. […]

November 27, 2011

1 Comment